China is considered one of the most technologically advanced countries in the world. Its manufacturing industry, which most businesses rely on worldwide, is taking a huge chunk of the country’s economy—and it’s not stopping anytime soon. China is also considered one of the largest countries in terms of land mass, housing billions of people today that contribute to its economy. With the richness of the country’s natural resources and job opportunities, it is easy to assume that every citizen is enjoying a good quality of life. But just like most countries, people also suffer from poverty.

In this article, we will discuss the lesser-known struggles of citizens in rural China, stories of real people, and the poverty reduction programs we have in place. Hopefully, we can raise awareness of this lesser-known issue.

China’s countryside houses 80% of its population. Unlike in cities, where factories are the main source of income, rural China relies on agriculture. A 2014 study shows that 70.17 million people in rural China live below the country’s poverty line of CNY 2300 (USD 314).

Illness is considered one of the main causes of poverty in China. In the same study, 42% reported that they became impoverished due to illnesses, while 14% are currently suffering from various health issues that weaken their ability to work, save, and provide for their families. There is a rural health insurance system set in place, which individuals utilize. However, certain illnesses are not entirely covered, leaving many parts of healthcare inaccessible to the poor, only pushing these individuals into a deeper vicious cycle of poverty.

In 2015, the poverty line was lifted from CNY 2300 to CNY 2,800 (USD 323-394), yet the same challenges remain. How then does this look in the day-to-day life of a rural Chinese citizen? We share Legu Meniuwai’s story, one of our Pig Farming program beneficiaries, who experiences the difficulty of living with an aging and ill family member.

Legu’s household consists of six people: her elderly mother-in-law, two sons, one daughter, and her husband. Their home is self-built and constructed thanks to a CNY 15,000 (USD 2,112) subsidy under the government’s poverty alleviation policies.

The family’s annual income comes from her husband’s labor work and their farm harvests which totals CNY 40,000 (USD 5,633) when combined. Her husband works away from home for most of the year, often stationed in other provinces to engage in different labor work like farming and tunnel construction, and usually returns home every four to five months. He brings home about CNY 30,000 to the family; while the other CNY 10,000 comes from Legu’s family’s land, which they use to grow peppercorns, yielding over 300 jin (about 150 kg) yearly.

Although their annual income is a seemingly decent amount, partnered with their resources, their family size still makes it very difficult to make ends meet. All of the family income is spent on home expenses, the elder’s medical bills, and children’s education. These overwhelming expenses make them even more vulnerable when one more person gets sick or encounters a financial emergency. Families like Legu’s are only one emergency away from extreme poverty. If there were a reliable medical system, Legu may have had less to worry about and would only focus on her household expenses and their children’s education.

Chinese Poverty Reduction Programs

Since the 1980s, the Chinese government has recognized the poverty within its borders and made efforts to reduce it. Despite multiple efforts, poverty is still the nation’s challenge. In 2015, they initiated the “Decisions of the Central Committee of the CCP and the State Council on Winning the Battle of Poverty Education.” It aims to lift 70 million people above the poverty line by the year 2020 and to ensure that China will be a “moderately prosperous society)

There are strategies to alleviate poverty in rural China, and these are as follows:

- Help villagers find jobs in booming industries (tourism and e-commerce) after occupational training

- Relocation of residents near areas prone to earthquakes and landslides

- Children must receive basic education and occupational training for sustainability

- Development of public health services in impoverished areas

- The elderly and disabled individuals must be eligible for social security disbursements

Challenges and Criticisms

Many critics see the project as more economically focused, which does not necessarily guarantee that people increase their quality of life, but rather respond to demands needed by their growing industries.

Wang Sangui, a professor from Beijing’s Renmin University, said that even with these efforts, the local government still needs to devise new options to alleviate poverty in rural China.

A sociologist and Professor from Central China Science and Technology University, Xuefeng, criticizes the likelihood of building industries in the development of these regions. He is also skeptical of the sociological changes these projects bring. Economic development does not always equate better quality of life for the Chinese folk below the poverty line.

Right now, our organization has been conducting efforts to bridge the needs of those under the poverty line and give them access to opportunities like education and livelihood through our training programs, scholarships, and livelihood opportunities.

Conclusion

While we remain optimistic that China will find more ways to help its poor in the future, the lives of women and children growing up need our help. That is why we partnered with our good friends in China to help spread positive impact in the lives of our beneficiaries. Learn more about our projects in China here. Or donate today to help the Chinese rural poor.

DID YOU KNOW?

20 January 2026

The Reality of Orphans in Nepal

In Nepal, orphaned children face high risks of exploitation and trafficking due to…

0 Comments8 Minutes

10 December 2025

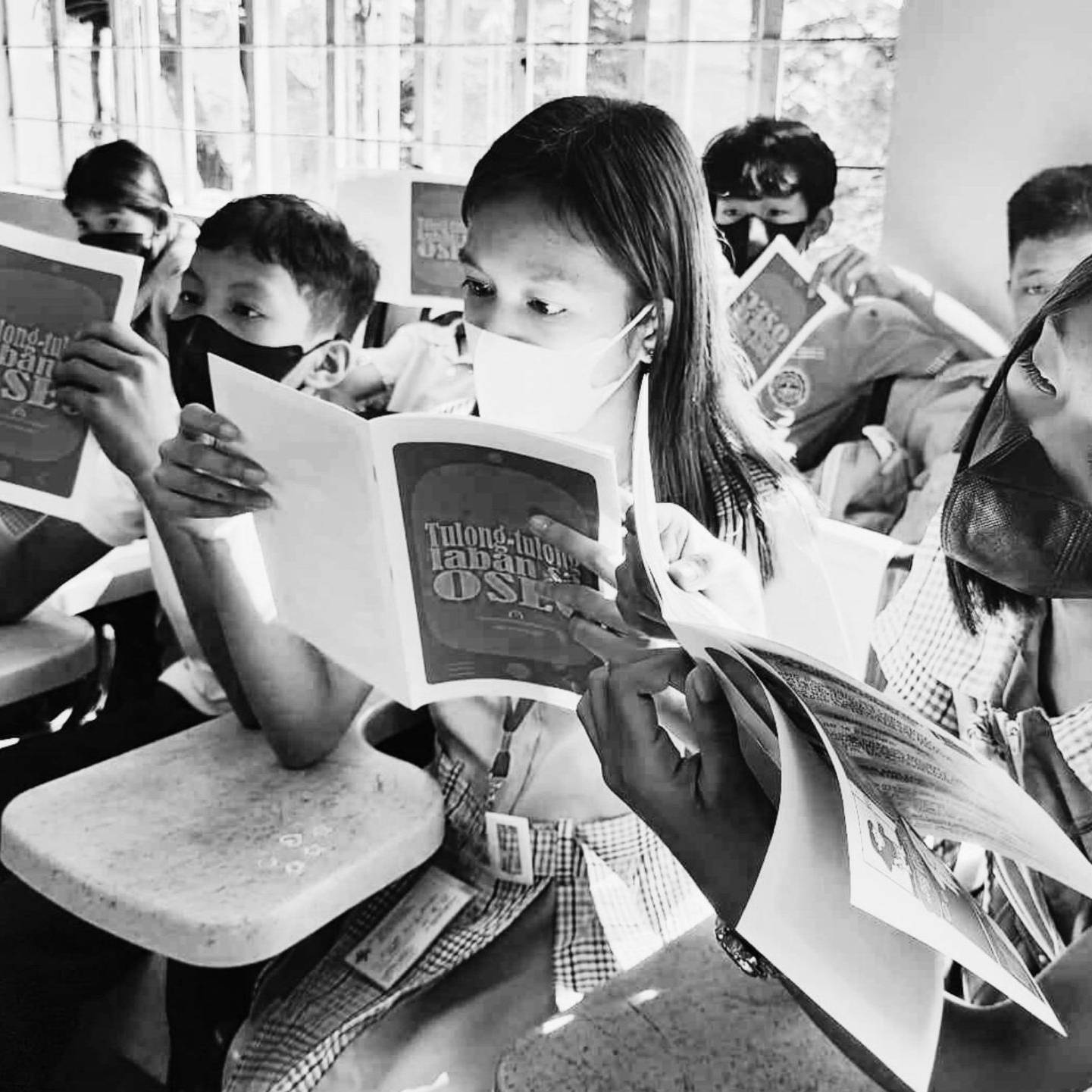

Fighting OSAEC: Policies, Global Leaders, and What More Countries Can Do

OSAEC is rising worldwide, and here’s what we can learn: strong laws, tech…

0 Comments14 Minutes

3 October 2025

Suspicious? Here are OSAEC Red Flags To Look Out For

Online child safety matters: learn how to spot OSAEC red flags, protect kids from…

0 Comments13 Minutes

4 September 2025

“Harmless” Posting? You Could Be Risking Children’s Online Safety

Some posts can put kids at risk. Protect children from OSAEC by keeping accounts private,…

0 Comments11 Minutes

11 August 2025

Life After Human Trafficking? Survivor Stories and What They Need

Rescue is just the first step, survivors need safety, dignity, and the chance to build a…

0 Comments13 Minutes

5 August 2025

What Is Child Exploitation? Definition, Types, and How To Help.

Child exploitation takes many forms: sexual, criminal, labor, online. Learn the signs and…

0 Comments9 Minutes

11 June 2025

Simply Captivating: Our 2024 Impact Report

In 2024, your support directly impacted 12,000+ lives across Nepal, China & the…

0 Comments10 Minutes

8 March 2025

Happy Women’s Day! Now What?

International Women’s Day is more than a day—it’s a movement for equality. Let’s educate,…

0 Comments11 Minutes

10 February 2025

What Is OSAEC in the Philippines?

Online Sexual Abuse & Exploitation of Children in the Philippines is a growing crisis,…

0 Comments8 Minutes